The Metropolitan Society of Natural Historians met in the late afternoon of March 24th, a cold, drizzly day, at the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) to be greeted by the ever-wonderful Dr. James Lendemer, a lichen specialist and assistant curator of Institute of Systematic Botany at the NYBG. This time, James invited us to see the marvelous herbarium of the Botanical Garden, where we not only learned how this astounding institution is run, but also how important it is for science and for many other scholarly activities. For example, the enormous collection of pressed dried plants and fungi is allowing us to reconstruct how the environment changed over the course of the last few hundred years. Sadly, much has been lost over the course of time. Lichens, which were found abundantly in the famous Palisades just across the lovely island of Manhattan, went extinct in this region due to air pollution.

When entering the herbarium, we passed by the immense collection of specimens, which were either sent or were received from scientific institutions from across the world – knowledge sharing at its best. Then, we entered the cold room, in which specimens, which are not fully processed, are temporarily stored to prevent insect damage, until they are ready to be shelved into the many drawers of the herbarium.

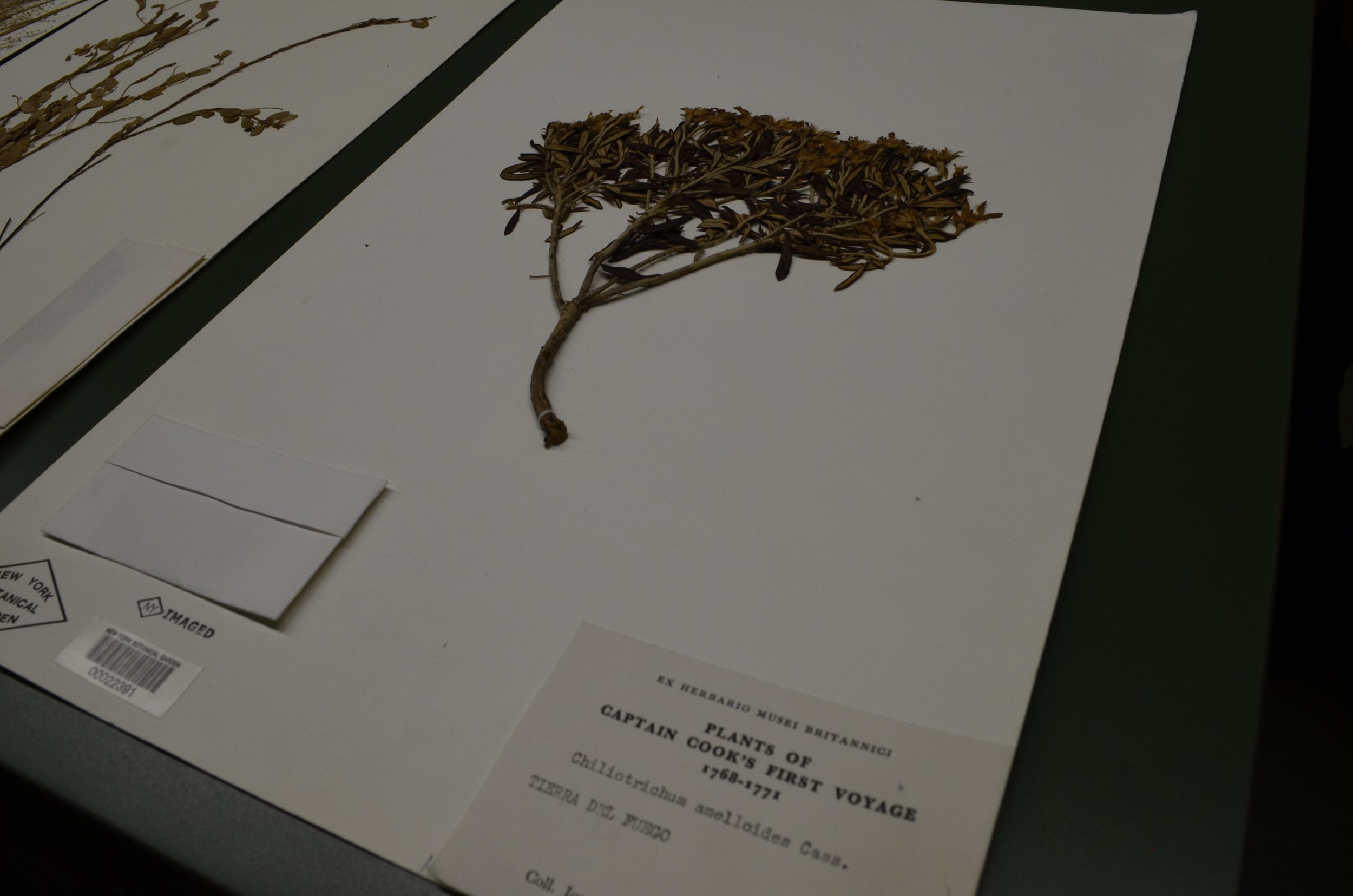

The herbarium itself is distributed among several floors – and among the collection, there are several treasures, many scientific, but also many equally important as for historical-sociological reasons. For example, we saw a liverwort, which was collected by no one else but Mr. Charles Darwin on his now famous visit to the Galapagos Islands. Interestingly, that liverwort is also considered a type specimen, thus it was used to describe and define the whole species. Many other type specimens are found in the NYBG Herbarium, the second largest of its kind across the globe (Kew Garden in England is #1 in terms of specimens). However, other treasures awaited us: plants collected by adventurous Alexander von Humboldt and his travel companion Aime Bonpland, famed ornithologist Audubon, and many more. Furthermore, we also were able to read a letter by the ingenious Thomas Edison, who tried to use an attached goldenrod plant to extract rubber from this species during World War I. Still in awe, Dr. Lendemer proceeded to show us a delightful loose sheet book with Mosses of Paris, as well as other bound books, which served as herbaria, before people realized that it might be easier to make comparisons if they are kept on loose sheets.

After these wonders, we learned about fungi, which were not only dried during preservation, but also hand-drawn and painted as a reference as dried specimens lose a lot of morphological information. The fungi, however, are stored in a cold room, as insects, like many humans, have a taste for those delicious morsels. Of course, we learned about lichens: 20,000 specimens are housed in the herbarium – and unlike many plants, they keep their stunning coloration throughout the centuries, which was demonstrated by beautiful specimen of Christmas lichen, among others.

Finally, we visited probably the most beautiful specimen housed in the herbarium. Intricate branching patterns, mesmerizing coloration – for the first time in our lives, algae appeared to us as astonishing artwork pressed on paper. On the way out, we were shown the “unknown cabinet”, specimens which have not yet been fully identified. It seems, there is plenty of more work to do at the NYBG Herbarium. While simple in technique, major discoveries can still be made with this century-old procedure, sophisticated tools are not needed but people who dedicate their time to this wonderful endeavor.

Some of these people dedicate themselves to make the herbarium collections available to everyone, including people outside of the USA or who have limited means to travel. Thus, a multitude of volunteers are dedicating their free time to take image of pressed plants and what not, which then will be uploaded on to the NYBG website, creating a ‘Virtual Herbarium’. This internet-marvel allows us now to look at specimens collected by Darwin, Audubon, and our own Dr. Lendemer, as well as many others. By the way, anyone can visit the herbarium and explore specimens, as long as you have a scholarly-artistic reason to do so.

We left the herbarium in awe, still astonished about what was hidden from us in this grand building of the New York Botanical Garden. Thank you, Dr. Lendemer, for another great tour!

To view more photos from this event, please visit our gallery. All photo credit goes to Harald Parzer.

To become a volunteer at the NYBG visit here.

Also check out Dr. Lendemer’s book, which is authored with Dr. Jessica Allen, former vice president of the MSNH: Urban Lichens.

Dr. James Lendemer is an Associate Curator at the New York Botanical Garden where he oversees the largest collection of lichen natural history specimens in the Western Hemisphere. He is also an Assistant Professor at the CUNY Graduate Center where he works with students pursuing careers in botanical science, especially lichenology and has also led outreach events for the MSNH. Although he has spent more than twenty years exploring lichens in the wild lands of America and abroad, recent collaboration with Dr. Jessica Allen, former vice president of the MSNH, led to urban exploration as well. Dr. Lendemer and Dr. Allen have recently published a book, Urban Lichens that allows identification of lichen species in eastern North America.